In my new book, I define digital portfolios as “dynamic, digital collections of information from many sources, in many forms, and with many purposes that better represent a student’s understanding and learning experiences.”

While a definition is great, I also sought to provide examples of digital student portfolios in action. Several teachers shared their work with me on using digital tools for authentic assessment. Next is an excerpt from the text in which a 2nd-grade teacher facilitates a writing conference with a student. It is followed by my explanation with new thinking.

Calleigh, a 2nd grader, sits down with her teacher, Janice Heyroth, to prepare for an assessment. This is a regularly scheduled conference during the middle of the school year; Janice meets with each student six times a year to reflect on a piece of writing in their digital portfolios. At the beginning of the year, students completed a reading and writing survey, which was uploaded and shared with students’ families via FreshGrade (www.freshgrade.com). The information gleaned from that survey gave Janice information about each student’s dispositions toward reading and writing. Questions such as “What types of books does your child enjoy reading on this/her own?” and “Does your child enjoy writing? Why or why not?” gave insights into how students approached literacy in their lives. It also informed her future instruction, such as generating writing ideas and topics students could choose to explore if they needed more support.

Elbows on the table, Calleigh props her head on her hands as her teacher spreads out some of her own writing. Because it is the middle of the school year, Calleigh’s folder already contains multiple compositions. Janice encourages Calleigh to locate a recently published piece she is proud of. She selects one, and then Janice starts off their assessment with a question: “So, what are some things you are doing well?”

Calleigh doesn’t hesitate. She states, “Handwriting.” Calleigh pulls an older piece of writing from her folder and compares it with a more recent entry to show the difference. Janice listens and smiles while she writes down Calleigh’s response in her conferring notebook.

Janice prompts, “What else?” and then silently waits and allows Calleigh the time she needs to look back at her writing and find other points to highlight. After a few seconds, she responds, “I don’t know.”

Janice acknowledges Calleigh’s honesty and follows up with more specific language. She says, “Well, I have noticed a lot of areas where I think you’re doing well in your writing. First, you stayed organized with your writing. Did you notice that?”

Calleigh tentatively nods.

Janice then says, “Do you know what I mean by staying organized in your writing?”

Calleigh hesitates and then smiles as she responds, “No.”

“Okay … did you stay on topic?”

“Yeah”

“What is your topic about?”

“Going to Florida.”

“Right. It’s all about going to Florida. Did you tell me about what you did first and go all the way through to the end?”

“Yes.”

The conversation continues, and while this assessment is taking place, the rest of the students in the classroom are busy independently reading and writing, working on self-guided vocabulary activities, or using computers to listen to narrated digital stories. At one point in the assessment, Janice starts to make a suggestion (“Would it have made sense … “), stops herself, and then restarts her inquiry: “Why did you start your real narrative in this way?” Calleigh shares that she started her story by describing an important scene during her visit to Florida. This is a strategy for developing a lead that she learned during whole-group writing instruction. Janice makes sure to note this connection between teaching and learning in her notebook.

The assessment closes with Janice asking Calleigh what she would like to continue working on with her writing. This time, she waits 15 seconds for a response.

Finally, Calleigh says, “Spaces.”

Janice pauses and then responds, “Actually, your spacing is fine. The same with your spelling and handwriting—everything looks great. Let’s take a look at your ending, though. ‘Our trip to Florida was fun and exciting.’ How could you have spiced things up and made your ending more memorable?”

Calleigh struggles with how to respond. Janice reminds her that endings can often resemble leads. With this information in hand, Janice makes a note to prepare future minilessons that address endings. Janice finishes up her time with Calleigh by showing her how to upload her writing to FreshGrade so her parents can see her work.

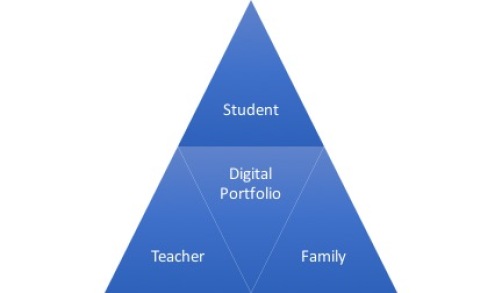

To summarize, this process of capturing, reflecting on, and sharing student work is a triangulated assessment. This is different than “triangulating assessments”, in which a teacher uses three assessment points to better evaluate a student’s level of growth or proficiency. The digital portfolio assessment process is triangulated because they have three audiences: the family, the teacher, and, most importantly, the student.

Here is how this assessment was triangulated:

- The family members heard and saw their daughter selecting her best work and reflecting on it. They now have a talking point with Calleigh when she gets home that evening about what she is learning. In speaking with other teachers, they have found that as parents hear the teacher conferring with their child, they start to take up this language and emulate it at home, such as when reading a book with them.

- The teacher was video recording the conference with her student. Knowing this was being seen by others, she likely made a more concerted effort to facilitate an effective assessment process. Janice also could go back to the video and watch it to evaluate her own instruction later on. She has time now, as scoring the writing is no longer necessary with the continuous process of portfolio assessment.

- The student was provided voice and choice in which writing piece to upload into her portfolio. She took her time because she knew her teacher would be asking her to provide a rationale for her selection. All of the questions from Janice were centered on Calleigh. She was the one doing the thinking, and the learning.

I don’t want to get too wordy in this post, so I’ll leave it here for now. I do want to revisit this concept of triangulated assessment (vs. triangulating assessments) in the future. With this initial thinking, it seems like teachers are working smarter and leading a more student-centered approach to assessment. Let me know what you think! – Matt